Building Decarbonization Legislative Roundup, 2023

a curated tracker and analysis of building decarb policies across the U.S.

Blog by Kristin George Bagdanov, Mgr. Policy Research & Knowledge Sharing

Graphics by Tiffany Vu, Research Associate

Table of Contents

Introduction

Trends & Trendsetting Policies

Trendsetters

New York

Minnesota

Oregon

Colorado

California

Trends

Limiting the Expansion of the Gas System

Standards and Codes to Phase Out Emissions in Buildings

Improving the Air Quality and Reducing Emissions in School Buildings

What’s Next for Building Decarbonization

Notes & Methodology

Introduction

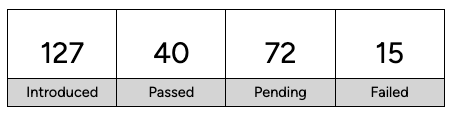

2023 has been a banner year for building decarbonization legislation. We’ve identified 127 bills and budget items across 25 states that support the rapid decarbonization of the built environment, varying from clean heat standards and workforce training programs to funding for heat pumps and energy bill assistance. Taken together, these bills represent a future of healthier buildings and communities as they promise to eliminate pollution and increase the habitability of homes for all people.

Below is a snapshot of the bills introduced and their categories, as well as a link to the full legislative tracker.

This year’s roundup is a bit more capacious than last year’s, as we’ve included pending, passed, and failed bills to offer a more comprehensive (yet curated) picture of what policymakers and advocates are proposing in various states. Read more about our methodology for what we included or didn’t include here.

Trends & Trendsetting Policies

(Expand to view full size)

Several patterns emerged when reviewing the nearly 130 building decarb bills across 25 states that were introduced in 2023. These trends include: limitations on the expansion of the gas system; new or improved building performance standards; building code modifications; and a suite of bills targeting school buildings and their indoor air pollution and emissions. Several bills across these categories mandated specific low-income protections and provisions while others included provisions for workforce development and labor standards.

We’ve also highlighted a handful of bills that we think are setting the national tone for building decarb legislation. This year’s trendsetting bills include a roadmap for reducing building emissions and a neighborhood-scale decarbonization bill in California; the All-Electric Buildings Act in New York; ending line extension allowances (LEA) in Colorado; an Omnibus Energy bill coupled with new clean electricity standards in Minnesota; and a massive Climate and Resilient Buildings package in Oregon. Even though some of these bills fell short of reaching the governor’s desk, they set the tone in their legislatures and communities by aligning stakeholders, socializing concepts, educating policymakers, and building momentum for success in future sessions. Rather than restricting our definition of success to session-by-session wins, we want to appreciate how certain policies shape the broader conversation about building decarbonization and soften the ground for future policies in multiple states.

Trendsetters

There were several standout bills this session that we think will set some new trends across the nation. Here are just a few of our favorites:

The All-Electric Buildings Act raises the bar for state-wide building decarbonization action. The bill makes New York the first state to legislatively commit to fully decarbonizing all new buildings. Adopted as part of the FY 2024 New York state budget, it requires new buildings under seven stories to be built all-electric by 2026 and taller buildings by 2029. This law is an important step toward meeting the greenhouse gas emission reduction mandates in the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). Passed on the heels of New York’s other trendsetting bill–the 2022 Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act (UTENJA)–these innovative policies position New York as a model for others working toward state-wide electrification and gas pipeline alternatives.

With a slim majority in the Senate, Minnesota advocates capitalized upon the window for passing meaningful legislation to reduce greenhouse gas (GhG) emissions and enable a way forward for building electrification by coupling an omnibus bill with new targets for clean energy. A GhG reduction target is a critical tool for aligning state agencies and programs while strengthening the case for building decarbonization: the cleaner our electricity is, the more effective building decarbonization is at reducing emissions. In addition to passing a 100% Clean Energy bill (HF7 /SF4) that promises 100% carbon free electricity by 2040, the Legislature passed a $115M State Competitiveness Fund bill (HF1656/SF1622) to prepare the state to take advantage of incoming federal dollars from the IRA and IIJA. In addition, they passed The Environment, Natural Resources, Climate, and Energy Omnibus bill (HF 2310*/SF 2438). Specific to building decarbonization, this bill promises $13M for heat pumps; $6.5M for electric panels (with 100% of costs covered for low-income households), and environmental review and permitting provisions to mitigate impacts on communities overburdened by pollution (via the Frontline Communities Protection Act). This suite of bills tees up the state for future policies like building performance standards, clean heat standards, and other innovative approaches to building decarbonization while also ensuring that the state can take full advantage of federal funding from the historic climate and infrastructure bills.

Oregon had a banner year for climate legislation, passing the Climate Resilience Package [which included the Resilient Efficient Buildings Package (HB 3409)], despite a 6-week walkout from Republicans that denied quorum and ground the Legislature to a halt until the very last moment. Regardless, advocates rallied for the passage of a historic suite of climate bills, including standout bills for building decarbonization, such as a statewide building performance standard (discussed later in this post) and Healthy Heating and Cooling for All. This bill sets a target of installing 500,000 heat pumps in homes by 2030 (which would mean a new heat pump in 25% of existing homes) and sets the stage for leveraging incoming federal incentive dollars to increase weatherization, heat pump adoption, and other clean energy retrofits. It also includes provisions that prioritize low-income and environmental justice communities (Climate Solutions). The success of the 2023 session is due in part to the foundation laid in 2022 when advocates passed a bill that authorized a Resilient Buildings task force. This task force helped build the broader coalition through sustained stakeholder outreach and engagement and ultimately shaped the policies that succeeded this year.

The Utility Regulation Bill (Removing Barriers to Clean Heat (SB23-291) eliminates a significant hurdle for downsizing the gas system–line extension allowances–which are essentially ratepayer funded subsidies for new gas hook-ups. According to Meera Fickling, Sr. Climate Policy Analyst at Western Resource Advocates, the Utility Regulation Bill succeeded in part due to how it sought to mitigate gas rate increases and volatility, an objective that convened a broad coalition due to this past winter’s historic gas prices. The bill: 1) eliminates gas line extension allowances by the end of 2023; 2) ends penalties for customers voluntarily terminating gas service; 3) directs Colorado Energy Office to study gas utility depreciation schedules and potential for stranded assets; and 4) directs the PUC to study how development in certain fast-growing areas drives gas infrastructure costs, and whether alternatives can be targeted to these areas to mitigate impacts. (Watch BDC’s National Policy Call on Colorado for more information on this bill.)

Carbon Emission Reduction Strategy: Building Sector (AB 593). This bill seeks to establish the first state-wide roadmap for cutting emissions from buildings in a way that maximizes benefits for low-income households, builds climate resilience for communities, and supports the workforce. Specifically, it directs the California Energy Commission, in partnership with state agencies, to identify an emissions reduction strategy for the building sector, complete with milestones, to advance California’s path toward carbon neutrality by 2045. While many states have economy-wide GhG reduction plans, most do not have industry-specific roadmaps that align state agencies and existing programs to collectively develop a plan to cut emissions. In addition, the bill offers a pathway for implementing “clean cooling,” as a quarter of Californians still lack access to air conditioning despite intensifying and life-threatening heat waves across the state. This bill underscores the importance of coordinated emissions reductions in buildings as well as the need for the state to incorporate extreme weather into its planning efforts. In addition, the bill prioritizes growing clean energy jobs and supporting family-sustaining wages. Part of a suite of decarbonization bills in the Upgrade California campaign, AB 593 will be carried into 2024 as a two-year bill and continue to align stakeholders and strengthen the coalition.

Another bill that we hope will set a new legislative trend is SB 527, the Neighborhood Decarbonization Program. Though held in committee, this bill was innovative in its approach to scaling-up building decarbonization. Through an equitable, community-driven process, the bill sought to create energy affordability, invest in clean energy infrastructure, prioritize low-income communities, and provide high-road jobs for utility workers. This wide-scale approach to shifting from a gas system to a zero carbon system can accelerate building decarbonization by upgrading entire neighborhoods rather than relying on households to electrify one at a time. This bill intended to provide direction for the CPUC to explore thermal energy network pilots and other neighborhood-scale approaches to building decarbonization and to reform state law to clarify California’s ability to decarbonize buildings through these approaches. Pathways to scaling up building decarbonization are still relatively new and this bill did a lot of heavy lifting by socializing new concepts and pathways for cutting buildings emissions. Importantly, it built a strong coalition that will continue to champion refined versions of this complex but essential approach to building decarbonization in future sessions.

Trends

Limiting the Expansion of the Gas System

Five states (CO, MA, NY, WA, VT) proposed bills that would establish limits on gas system expansion plans, costs charged to ratepayers, and emissions produced by existing gas infrastructure.

Enacting and Strengthening Clean Heat Standards

This year we saw the passage of a new Clean Heat Standards (CHS) in Vermont as well as legislation that proposes to improve and complement existing Clean Heat Standards in Colorado (2021) and Massachusetts (2022). The previously described Colorado law–Utility Regulation Bill (Removing Barriers to Clean Heat) (SB23-291)–complements the existing CHS by eliminating subsidies for new gas system hookups; the Massachusetts bill seeks to curtail the definition of “clean heat measures” to scalable, zero-emission decarbonization solutions; and the Vermont law establishes a new Clean Heat Standard.

Clean Heat Standards (CHS) are a new approach to limiting emissions from the gas system. They require the gradual reduction of emissions from heating services (typically gas utilities) and offer credits based on the tons of GhG reduced. They are similar to Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) in that they are both clean energy performance standards but CHS focuses on buildings whereas RPS focuses on power generation. Several “clean heat measures” can be used to reduce emissions, including weatherization, heat pump technology, thermal energy networks, and low-emission fuels. There is a range of acceptance and debate with regard to which of these measures should be used to meet the CHS. Areas of intense debate amongst stakeholders include the use of hydrogen and RNG as clean heat measures.

Massachusetts

A central challenge of shaping and enforcing a CHS is the debate over what is considered “clean” heat, as evidenced by proposed legislation in Massachusetts. In June 2022, the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan (CECP) tasked the Mass. Dept. of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) with developing a CHS. And in November 2022, the Commission on Clean Heat issued a report recommending that Mass DEP initiate a regulatory process to establish the CHS. Currently, MassDEP is hosting technical sessions to contribute to the development of the CHS. Meanwhile, advocates have proposed legislation to add guardrails to the standards. An Act Relative to the Clean Heat Standard (H.3694) seeks to exclude hydrogen and renewable natural gas from the acceptable fuels that gas companies can count as clean heat measures.

Vermont

Vermont’s legislature recently passed a CHS called the Affordable Heat Act (S.5), reversing the governor’s veto from the previous session to do so. The legislation will now direct the Public Utilities Commission to initiate a rulemaking to implement it. The Vermont Natural Resources Council explains what this will entail: “a 2-year process to design the program, including robust opportunities for public engagement, as well as studies to ensure we better understand questions like how the program will impact energy costs.” Following the program’s design, the legislature will have to vote on the proposal in 2025.

Intervening in the development and implementation of these clean heat standards in MA, CO, and VT will be critical to ensuring that scalable, zero-emission decarbonization measures take precedence over emissions reductions pathways that depend on RNG and hydrogen.

Creating Thermal Energy Networks, Utilities, and Workers

Thermal Energy Networks (TENs) are central to a just and equitable transition as they offer gas utilities and workers a pathway into the clean energy future. While utility-owned TENs are still a new pilot-only configuration, more and more states are passing laws to create the necessary regulatory pathways to grow this important approach to building decarbonization.

In Colorado, the Thermal Energy Act (HB23-1252) modifies the state’s recent clean heat standard by stipulating that thermal energy networks can be counted as an acceptable “clean heat measure” to help utilities meet their GhG reduction goals. In addition, the law mandates that large gas utilities (serving more than 500,000 customers) propose at least one thermal energy pilot by September 2024. It also establishes labor standards for state or public university-owned thermal energy projects. The Colorado PUC will be tasked in creating rules around the regulation of this technology, determining if additional legislation is necessary to facilitate the development of thermal energy, and consider the impact that the proposed pilots will have on the state’s utility workforce.

A bill under consideration in Massachusetts, An Act Relative to the Future of Clean Heat (H.3203/S.2105), seeks to create a pathway from business-as-usual gas company expansion and emissions to the Commonwealth’s net-zero by 2050 target through neighborhood-scale decarbonization. This policy seeks to empower regulators to allow gas companies to act as thermal energy companies, akin to New York’s 2022 UTENJA bill. This transformation of purpose–delivering heat, but not gas–would help meaningfully transform gas workers and companies for the clean energy future while scaling up building decarbonization to meet both climate urgency and emissions reduction timelines.

According to advocate briefs, including the Gas Transition Allies, the bill would also: 1) allow gas companies to install thermal energy networks using their existing workforce and rights-of-way 2) Mandate gas transition plans to non-emitting thermal energy at a neighborhood-scale 3) Prohibit depreciation of gas infrastructure past 2050 4) Use Mass Save and ratepayer funds to upgrade and weatherize existing buildings with electric appliances 5) Enable gas companies to sell, lease, and install electric appliance to replace gas ones 6) Requires the Dept. of Public Utilities (DPU) in gas system planning to consider non-emitting alternatives to gas infrastructure. This important bill is one to watch the rest of the session, which will conclude in July 2024.

Protecting Ratepayers and Eliminating Line Extension Allowances

Bills from Colorado and New York sought to revoke the subsidy that gas companies charge to existing ratepayers when they hook-up new customers. Line extension allowances (LEAs), as they’re called, mask the true cost of the gas system by socializing some of its costs to existing ratepayers, thus making the economic argument for adding gas to new construction work in their favor. As discussed previously, Colorado’s Utility Regulation Bill (SB23-291), which was signed into law this summer, will end line extension allowances by the end of 2023 and make it easier for customers to disconnect their buildings from the gas system. Bills from Massachusetts and Washington propose ratepayer protections and pipeline moratoria to slow the growth of the gas system.

Another bill that is showing exceptional promise in New York is the NY HEAT Act (A4592A / S2016A). This session advocates made significant progress on the bill, which would provide the Public Service Commission with the authority and direction to align gas utility regulation and gas system planning with New York’s Climate Law mandates; eliminate gas line extension allowances; and codify the state goal that low-to-moderate income customers are adequately protected from bearing energy burdens greater than 6% of their income. This bill would also amend the “obligation to serve” rules to no longer require gas service, but instead allow utilities to provide heat. Thanks to a broad coalition of advocates, the bill passed the Senate just as unprecedented smoke from Canadian wildfires blanketed the city, reminding everyone of the urgency of climate change legislation like this. While the bill did not pass in the Assembly, advocates are optimistic about its momentum; it now has 70 sponsors in the Assembly and advocates are working to see its key provisions included in Governor Hochul’s upcoming budget priorities.

Two bills under consideration in Massachusetts propose to protect ratepayers from gas pipeline expansion costs (H 3169 / S 2138) and establish a moratorium on new gas system pipelines altogether (H 3237 / S 2135). It remains to be seen how much success these bills will have; versions of the H 3169 have been proposed each session for the past several years.

Finally, a bill that did not advance in Washington (HB 1589) proposed to limit the expansion of the gas system by banning gas companies serving more than 500,000 retail customers from providing gas to new construction.

We’re likely to see new iterations of gas expansion moratoria and line extension bills, clean heat standards, and proposals to transition gas utilities to thermal energy utilities this next session as protecting ratepayers, cutting gas system subsidies, removing regulatory barriers, and curtailing infrastructure and fuels that conflict with state-mandated emissions reductions targets are top priorities for building decarb advocates across the U.S.

Standards and Codes to Phase Out Emissions in Buildings

Building Performance Standards

Seven states proposed legislation for new or modified building performance standards (BPS), a tactic for progressively reducing emissions and energy use in existing buildings, especially large commercial spaces. This year, Oregon joined Maryland (2022) and Washington (2019) in having a statewide BPS and Colorado (2021), which has a statewide energy-use benchmarking requirement, in addition to the many local jurisdictions with a BPS in place. California made strides toward a statewide BPS with a bill that will create a strategy for large-building emissions reductions.

While many BPS bills are still pending, Oregon succeeded in passing a BPS for large commercial buildings as part of its Climate Resilience package (HB 3409), which included four building decarbonization policies. Oregon’s BPS was modeled after Washington State’s 2019 BPS but set a lower square footage threshold to capture more buildings in Tiers 1 and 2. Tier 1 buildings, which are required to comply with the standard, include commercial buildings 35K sq. ft. and up (excluding multi-family, hospitals, schools, and universities); Tier 2 buildings, 20K-35K sq. ft., are incentivized to comply on a voluntary basis but are required to at least benchmark their energy use. This flexible standard offers several pathways for buildings to reduce their energy use over time and is expected to cut emissions in tens of thousands of existing buildings.

California passed a bill that sets the stage for implementing building performance standard for large buildings (SB 48). The Building Energy Savings Act directs several state agencies (Air Resources, PUC, Housing and Community Development) to develop an energy and emissions reductions strategy for large commercial buildings of over 50,000 square feet, which comprise “53% of total commercial building energy use,” according to Environment California. By utilizing existing benchmarking data, these state agencies will coalesce around a plan for how to reduce emissions from large existing buildings in order to meet the state’s existing climate targets.

Two pending bills in Massachusetts seek to create a BPS that aligns with the timeline and emissions-reduction goals of the Global Warming Solutions Act (H3192/ S 2144 and H 3213 / S 2178). A bill from Rhode Island (S 166 /H5425) that was held for further study laid the foundation for a future BPS bill by establishing goals for tracking energy use and emissions in residential and commercial buildings. Minnesota’s successful Energy Omnibus bill (HF 2310, 366.7) will require the establishment of an energy benchmarking program for buildings 50K sq. ft. and up and hopefully pave the way for a future building performance standard based off of data collected through this program.

Maryland’s proposed modification to its BPS also did not progress this session but was unique in terms of how it tried to eliminate fossil fuels from the efficiency equation altogether. The Maryland Building Performance Standards–Fossil Fuel Use and Electric-Ready Standards bill (H 1134) would have required buildings to meet emissions reductions targets without fossil fuels. This bill sought to address the gap between BPS and electrification–namely that while these standards are effective at reducing emissions and energy use in existing buildings, these targets can often be met with more efficient gas appliances and weatherization and therefore do not directly address decarbonization goals to prune the gas system and fully electrify buildings. It is likely that we will continue to see a range of BPS legislation in the coming years as more states must address existing building emissions to meet their economy-wide emissions-reduction targets.

Electric and Efficient Building Codes

A reliable path to reducing building emissions is to update a state’s base energy code to comply with the most recent IECC code for residential buildings and the most recent ASHRAE code for commercial buildings, an approach that ensures new buildings are getting progressively more efficient. This year, eleven states took a diverse set of approaches to modifying and updating codes. Some simply updated their state’s base code to the most recent IECC, while others proposed policies to prohibit gas appliances in new construction, incorporate embodied carbon emission standards into existing codes, or grant authority to local jurisdictions to make clean energy updates to their local building codes.

Of the bills that passed, perhaps the most significant decarbonization bill is New York’s All Electric Buildings Act, as discussed earlier, which was the first state-wide all-electric new construction law. For context, in 2022 Washington became the first state to incorporate building electrification mandates into statewide residential and commercial codes by requiring electric space and water heating in new construction. New York’s law takes electrification one step further by prohibiting the installation of all fossil fuel equipment in new construction.

California is the next state moving toward a potential all-electric building code, with its soon-to-be-updated 2025 Energy Code. The cities of California agree that it’s time to align state code with the decarbonization measures that many municipalities have already undertaken; in fact, 25 cities and local governments recently sent a letter to Governor Gavin Newsom advocating for zero-emission new construction building standards.

In Oregon, the successful “Build Smart from the Start” bill, part of its Resilient Efficient Buildings Package, improves building codes for new construction and codifies an Executive Order that targets 60% improvement in energy efficiency for new buildings (from 2006 baseline); the bill also gave direction to work with Dept. of Environmental Quality to look into embodied carbon and to explore indoor air quality further.

States that committed to updating their codes to match or exceed IECC include Rhode Island, which requires the state to adopt the most recent IECC code, beginning with the forthcoming 2024 code with electric-readiness provisions. Utah updated their state code to the 2021 version of the IECC.

Minnesota’s omnibus labor bill (HF 2755/ SF2782) included requirements to update the commercial code, specifying that, beginning in 2024, each edition of ASHRAE 90.1 (or a more efficient standard) must be adopted. Furthermore, the commercial energy code “in effect in 2036 and thereafter must achieve an 80 percent reduction in annual net energy consumption or greater, using the ASHRAE 90.1-2004 as a baseline” (SF2782, 54.29).

Other policies still pending include a bill in New Jersey that would grant the authority to municipalities to ban gas hook-ups in new construction (A3185, a carry over from the 2020-21 session), a power they do not currently have. Hawaii proposed a similar bill (H835) that would have instituted a state-wide ban on gas appliances in new construction, but that bill has been deferred.

Improving the Air Quality and Reducing Emissions in School Buildings

Public schools offer a unique opportunity for achieving efficiency and decarbonization goals. Upgrading these publicly owned buildings or constructing them as all-electric from the start will drastically improve the health of students and staff through improved indoor air quality (IAQ) and reduced emissions. Several of the bills that seek to improve IAQ and HVAC filtration systems also have momentum from the COVID-era urgency to reduce the spread of viruses and from the uptick in unhealthy air days due to wildfire smoke.

Seven states proposed bills to address school air quality and/or energy efficiency. The proposed policies include:

- creating a “master plan” for schools that would include priorities, benchmarks, and milestones for health, resilience, and decarbonization of public school campuses and support facilities (CA–passed);

- developing policy recommendations on safe indoor air through research as well as taking an inventory of heating and cooling equipment in K-12 schools (CA–passed);

- requiring net-zero new construction or renovations for schools (CT–pending);

- creating a net-zero renovation fund for schools and other public buildings (MA–pending);

- offering zero-interest loans to schools for clean energy upgrades (ME–pending);

- assessing existing HVAC systems in schools (NY–pending);

- studying indoor air quality and HVAC systems (OR–passed); and

- establishing indoor ventilation assessment standards to reduce transmission of airborne viruses and exposure to indoor air pollutants; (New Mexico–failed).

Upgrading schools to align with new emissions and efficiency standards will make them healthier for the students, teachers, and staff who spend so much time inside these buildings.

What’s Next for Building Decarbonization

There is more to decarbonizing the built environment than passing bills, but it is an effective tool to create widespread change. Even for policies that don’t succeed, their introduction can help socialize new concepts and gather support that will make them successful in future sessions. For example, in Minnesota a bill to support electrical panel updates was introduced last session, where it initiated important conversations but failed to pass until this session. Many of the bills we are tracking are changing the landscape of building decarbonization even when they don’t make it into law.

Next year, we hope to see the passage of NY HEAT, more clean heat standards, more electric-only new construction, more high-road job standards, more provisions to protect low-income communities, more policies to improve indoor air quality and educate consumers about the harms of gas stoves, as well as policies that focus on scaling-up building decarbonization at the community- and neighborhood-level through thermal energy networks and thermal energy utilities. And, with the imminent roll out of federal funding, all eyes will be on state energy offices and the complex network of climate advocates and organizations to ensure that this money is leveraged to the fullest extent. An infusion of cash from the federal government is not enough to get buildings to where we need them to be to meet greenhouse gas reduction goals or to meet the increasingly volatile climate effects that make clean heating and cooling a human right. But with the right ecosystem of legislation, regulation, advocacy, and education we can turn this federal seed money into solid ground for the future of building decarbonization.

Sign up for our newsletter

Like what you’ve read? Get it straight to your inbox by signing up for our DecarbNation newsletter here.

Read back issues of DecarbNation

Issue 4: Neighborhood-Scale Decarbonization: A framework for decarbonizing the built environment at scale

Issue 3: Home on the Range: How policy is shaping the transition towards electrified kitchens

Issue 2: The Future of Gas: A Summary of Regulatory Proceedings on the Methane Gas System

Issue 1: Building Decarbonization Legislative Roundup, 2022

Notes & Acknowledgements

Methodology

As a rule, we have only included bills in the tracker that in some way would enable building decarbonization. Therefore, this tracker does not include new “preemption” bills or policies that would block decarbonization measures.

We have also tried to only include bills that directly touch buildings through emissions reductions, air quality measures, codes and standards, workforce development, environmental justice provisions, regulations, gas system infrastructure limitations, relevant cost and funding mechanisms, and rebates or subsidies for technologies and appliances. Meaning that, for the most part, we are not including policies related to supply-side issues or complementary technologies like solar panels and electric vehicles. The exception to this rule is that we are including any new or modified state greenhouse gas (GhG) reduction goals as these policies have far-ranging effects on the success of decarb legislation.

In addition, we’ve only included bills that had meaningful sponsorship, made it into committee, and/or were significant due to the difficult political climate in which they were introduced. For example, we’ve included a failed single-sponsor bill from a Democrat in Arkansas that seeks to create an “Advanced Electricity Jobs Task Force” because the bill acknowledges the movement toward zero-emissions infrastructure and seeks to push an oppositional Legislature toward carbon-free goals via an economic argument. Noting this approach may be helpful when strategizing for building electrification-friendly legislation in less progressive states.

Finally, the decision of what to include and what to exclude is of course subjective. We are happy to consider a bill that we’ve missed and that you think should be included. Our goal is to provide some understanding of the depth and breadth of building decarbonization bills throughout the U.S. so that we can more fully understand the trends, patterns, and scope of the movement.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the many advocates and organizations who maintain aggregators and newsletters that allow us to identify and synthesize these policies into a broader picture of our movement. Links to these sources are included in the tracker. Special thanks to the following advocates, whose conversations and presentations informed this analysis:

- Ben Butterworth, Acadia Center

- Allison Considine, BDC

- Joe Dammel, Fresh Energy

- Meera Fickling, Western Resource Advocates

- Greer Ryan, Climate Solutions

- Robin Tung, BDC