Community Action Network (CAN) Director Derrick Miller and Ann Arbor Mayor Christopher Taylor cutting the ribbon with members of the Bryant community to celebrate the Bryant Community Center becoming a resilience hub.

|

Quick stats:

|

Introducing Ann Arbor’s Bryant Neighborhood

“We came into thermal energy networks without the intention of doing thermal energy networks. But we had a climate goal to decarbonize an entire neighborhood: Bryant.”

Joe Lange, Senior Energy Analyst, City of Ann Arbor

Ann Arbor, Michigan, is home to 120,000 residents, a Big Ten university, and an ambitious climate agenda: A2ZERO, the city’s plan for a just transition to carbon neutrality by 2030.

For three years, Ann Arbor has pursued neighborhood-scale decarbonization in Bryant, an environmental justice community where 75% of households qualify as low-income and over a third are energy-burdened.

Many of Bryant’s 262 homes, built in the late 1960s and early 1970s, require critical maintenance to improve poor insulation, leaky windows, and outdated appliances. One particular resident contended with gas leaks, flood damage, and mold, which was exacerbating her lung condition and “killing her in the long term,” explains Ann Arbor’s Senior Energy Analyst, Joe Lange. Situations like these, combined with A2ZERO’s ambitious goals, made Bryant a priority for equitable decarbonization.

Fundamental Community Partnerships

For three years, the city’s efforts in Bryant have been implemented in partnership with Community Action Network (CAN), a community development nonprofit in Washtenaw County. CAN runs seven centers throughout the county, including in Bryant.

This partnership is crucial. Municipal governments and utilities considering a thermal energy network (TEN) “must work with a pre-existing organization that is already trusted by the community,” Lange emphasizes. “You can’t go into a neighborhood and say ‘Guess what, we’re putting in a geothermal system.’ You need trusted partners. This is fundamental: there is no path forward for a project like this without that.”

(Left to right) Amaya Hall (Ann Arbor Office of Sustainability and Innovation, AmeriCorps), Jordan Larson (Ann Arbor Office of Sustainability and Innovation), and Krystal Steward (CAN) canvassing the neighborhood to talk to residents about the geothermal project and invite them out to community meetings.

Health, Safety, and Remediation

Ann Arbor secured $2 million from the Michigan State Housing Development Authority, as well as additional funding from Builders Initiative, the McKnight Foundation, and other foundations to decarbonize Bryant, beginning with home assessments and upgrades. The city and CAN also worked to enroll residents in the Weatherization Assistance Program for additional weatherization funding. Energy assessments analyzed health and safety metrics as well as energy efficiency in every home.

About 40 homes have completed upgrades so far, and funding is available for 80+ homes. The work is designed to address health, safety and affordability. For example, a resident whose home had a gas leak received comprehensive upgrades: basement encapsulation, gas leak repair, insulation, an upgraded electric panel, new appliances, new windows, and solar panels. A ballpark estimate for this type of work is approximately $55,000, says Lange, but thanks to grant funding, the cost to the resident was $0— and her monthly utility bills dropped from $200 to $25.

Stumbling Upon Thermal Energy Networks (TENs)

Ann Arbor staff first explored decarbonization with air-source heat pumps (ASHPs). The options were technically feasible, even in Michigan’s cold climate. But high electricity rates made their projected operating costs prohibitive, especially compared to low methane gas rates. Even after weatherization, residents’ bills would likely increase, which was “unacceptable” to A2ZERO’s mission, says Lange.

Seeking a more affordable solution, the team explored geothermal heat pumps and eventually “stumbled upon” geothermal networks. This changed the math, especially when coupled with ongoing weatherization and solar installation efforts. When stacked with those initiatives, the geothermal network is projected to reduce residents’ energy bills by 77%.

In 2022, Ann Arbor’s Office of Sustainability and Innovation secured a Department of Energy Community Geothermal grant to conduct a feasibility study for a geothermal network. Ann Arbor began working with engineering firm IMEG to design the network.

“You can’t go into a neighborhood and say ‘Guess what, we’re putting in a geothermal system.’ You need trusted partners. This is fundamental: there is no path forward for a project like this without that.”

Joe Lange

Ongoing Community Engagement

Ann Arbor and CAN staff and volunteers spent 12 months discussing the geothermal network with Bryant residents (and outreach is ongoing). Efforts were supported through AmeriCorps interns, CAN staff, and a full-time city staffer hired for outreach on Byrant’s decarbonization plans. Bryant residents played a role in hiring the full-time city staff member, selecting from a group of finalist candidates.

AmeriCorps and CAN canvassed the neighborhood four times with flyers and door-knocking campaigns. Ann Arbor staff participated in events in Bryant “at least monthly, and closer to two or three times a month,” says Lange. Staff integrated geothermal education and outreach into pre-existing community events, such as a back-to-school barbecue, community cleanup days, and a trivia night.

To visualize the geothermal network, students from the University of Michigan developed a 3D model that accompanies city staff at all geothermal-related events. It lives permanently in the Bryant community center lobby.

A model of a district geothermal system created by students at the University of Michigan and accompanying materials to help residents learn about geothermal.

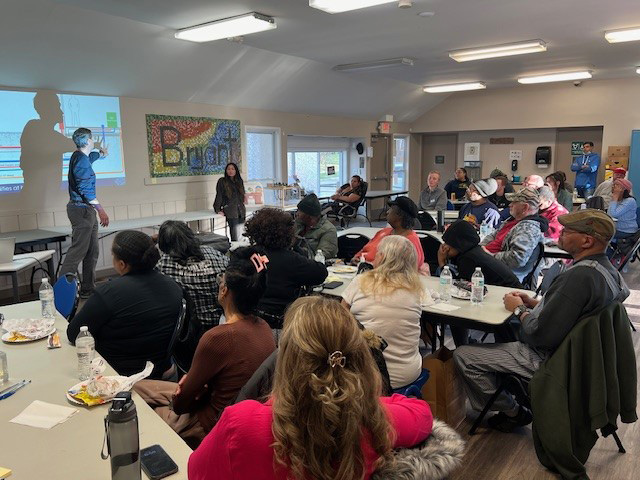

The city and CAN hosted three community design charrettes for residents who desired more involvement in the geothermal network’s ownership and design. Each charrette welcomed 40-45 people. Charrettes covered concerns over what level of disruption was acceptable and which heat pumps were the most attractive options for homes, and community members stated their firm preference for local ownership over the network.

Again, the relationships of CAN staff proved instrumental. Lange remembers an example: “I’ll never forget Krystal [CAN staff member] asking someone in the community center, ‘Are you coming to the geothermal charrette tonight?’ And she said, ‘Krystal, I don’t care what it is—if you say I should come, I’ll be there.’”

A geothermal charette with residents to learn about the system design and to give feedback to shape the project.

Choosing an Ownership Model

Bryant is served by DTE, an investor-owned utility that provides gas and electricity. The city’s 20-year gas franchise agreement expires in 2027 and is under renegotiation. The city’s electric franchise agreement with the utility is in perpetuity.

The issue of timing affected the city’s ownership decision. DTE has their own climate commitments, and Michigan legislation requires utilities to provide electricity from carbon-free sources. However, that legislation does not affect DTE’s gas business, and both state and utility climate goals are on longer timelines than A2ZERO, Lange explains. Additionally, Michigan currently lacks legislation that provides regulated utilities with the authority to own and operate geothermal networks, which is a barrier to a utility-owned geothermal network.

A public power movement in Ann Arbor proposes full municipalization of DTE’s infrastructure, but this also has challenges. It would be financially challenging, and it would take past 2030 to implement, which is A2ZERO’s deadline for carbon neutrality.

Among A2ZERO’s proposals was a municipally-owned Sustainable Energy Utility (SEU). This model is a supplemental city-owned utility that would provide 100% renewable energy to subscribers and could take on sustainability projects that DTE is not prepared, or able, to complete—like a geothermal network. This model would “provide residents with a choice in a way that’s more accessible than transitioning an entire grid at once, or even over a few years,” says Lange. Best of all, it honored Bryant residents’ preference for local ownership.

Building the Sustainable Energy Utility

In November 2024, 79% of Ann Arbor residents voted in favor of Proposal A: Creation of a Sustainable Energy Utility. The language in the proposal outlined a “supplemental, community-owned energy utility that provides 100% renewable energy from local solar and battery storage systems installed at participating homes and businesses in the city.”

Technically, notes Lange, the city did not require a vote to establish the SEU; Michigan law permits the city to establish its own utilities. However, Ann Arbor staff and officials wanted the SEU fully and democratically legitimized through a vote of the people.

Ann Arbor will own, operate, and maintain the geothermal network under the auspices of the SEU. Geothermal industry experts have provided letters of commitment to assist with its operation while the city hires and trains staff and builds organizational capacity to run it on their own. Initial funding for the geothermal system will come from the Department of Energy grant.

Initial funding to establish the SEU as a whole could come from philanthropic or federal grants, existing City funds, bonding, a power purchase agreement, impact investors, or a large customer (or several)—or a combination of all of these approaches, says Lange. Afterward, it will be entirely subscription-based. A 2024 report from Strategen indicates that the SEU “can be financially viable for the city, generate cost savings for Ann Arborites, increase resilience, and reduce emissions,” but two critical variables for financial viability include a minimum size of 20 megawatts and an interest rate below 6%.

The SEU ownership model provides crucial benefits for Bryant’s geothermal network:

- First, it goes “further, faster,” says Lange. The city can invest immediately in clean energy on its own ambitious timeframe.

- It improves equitable decarbonization. “Asking everyone in the city to install geothermal on their own is unfeasible,” says Lange. “An SEU, as a public utility, can deploy these systems much more equitably than traditional market forces.” On-bill financing is permissible in Michigan, so if a subscriber to the SEU wanted a ground-source heat pump, for example, they could get one with no up-front cost through the SEU and pay for it over time.

- The city can prioritize employing local labor for solar and appliance installations.

Integrating New and Existing Infrastructure

The SEU will be completely isolated from DTE’s infrastructure, and will own its own distribution system, wires, and lines, Lange explains. Residents will still be connected to the DTE grid to fill in gaps that the SEU cannot meet, but no power from the SEU will flow to DTE.

The city will own all pipes and meters for the geothermal network. The ownership of in-home heat pumps remains under discussion, Lange says. Bryant residents will not be asked to pay for their own heat pumps.

There are other challenges—namely, the future of the gas distribution system. Currently, DTE’s gas pipeline network is expected to stay in the ground, resulting in the geothermal distribution network needing to go around the gas pipes.

Drilling at the Bryant Community Center for the Center’s geothermal system (this will eventually connect to the larger geothermal network).

Looking to the Future

In December 2024, Ann Arbor was selected by the Department of Energy’s Community Geothermal Grant program for $10 million to construct the geothermal network. The new presidential administration has made the future of this funding uncertain, but the long-term plan is for the SEU to become a self-funding mechanism, explains Lange, “doing more as we get more subscribers.”

“[The geothermal network] is a great opportunity for this community, but we want to do this on a broader scale,” Lange says. “There’s a huge impact here, but it’s 262 homes, and we have a community of 120,000.”

The city is working with contractors to understand and test the feasibility of geothermal networks city-wide.

Of key importance is sharing their lessons and story with other towns. Sharing information is a key ingredient to success and replicability, Lange says: “A core goal of ours is replicability, as well as the opportunity to learn from others.”

Thank you to Joe Lange for your contribution to this case study. If you are interested in learning more, you may contact Joe Lange at jlange@a2gov.org.